“What do you think of the weather here?” Leifer asks. He always tells me it’s the best weather—up in the mountains. Now he’s looking for affirmation. The days are warm, and the nights are cool. The water is crisp, coming down from the glaciers in the mountains. We don’t need heat or air conditioning.

It’s a cash culture here. Exact change is usually preferred. I haven’t used my credit card once. Leifer often tells me whether something is a good price or not. In America, he’s explaining how expensive something is, debating whether we really need it or can live without it. Here, prices vary widely. Some things are much cheaper in Lima. Diapers, for instance—we can get nearly twice as many for the same price compared to Mancos.

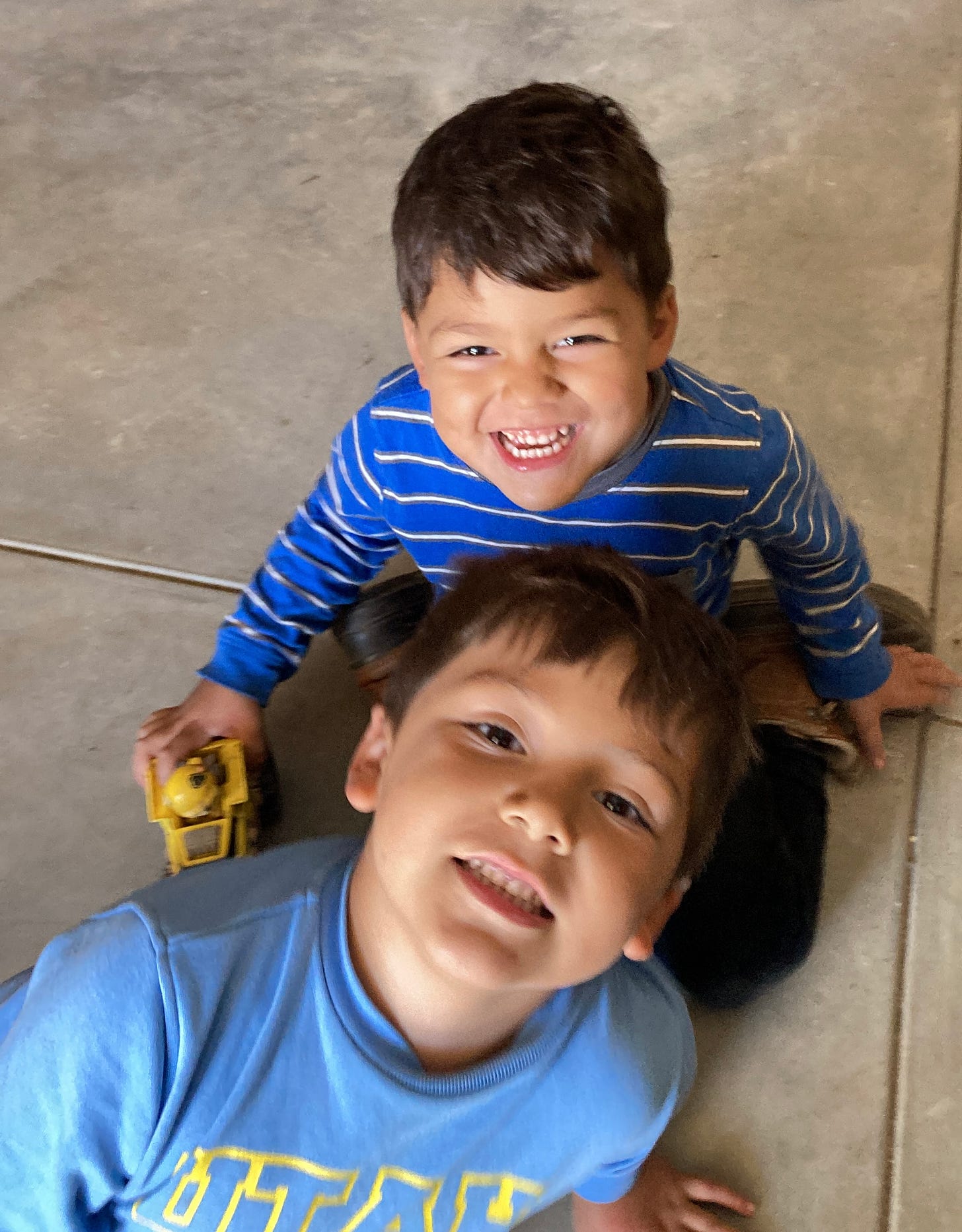

Over breakfast, I have Leifer ask Abuelita who the kids resemble more—him or me. She says they look Peruvian. She says Lucca’s round face reminds her of her firstborn son. Then I wonder what happened to her parents. Her mother died in her 40s—likely from a stomach ulcer, though she was never diagnosed. Her father died in his 60s from a fall off a ladder. This relationship mattered to Leifer. He was close to his grandfather, and it was hard on him when he passed. That relationship was one of the first stories Leifer shared with me. As a boy, Leifer didn’t want to go to school and began skipping. His mother sent him to live with his grandfather, who gave him structure. He would wake Leifer early to run, then sit him at a table to study. Leifer respected him—and feared him a bit too. With his father gone for work, that masculine presence was important. I think of that often now, raising three boys of my own. I believe it’s vital for them to have strong male role models so they grow into responsible, caring men. I worry history will repeat itself, with Leifer traveling far distances from us like his father had to.

“Come, come (eat, eat),” Abuelita tells the boys. For her, eating is the barometer of health. If they’re eating, they’re okay. If they’re not, she worries. Her eyes are warm and loving. She often laughs—just like Leifer. I’m at ease when my boys are peacefully asleep at night.

Leifer went down to Huaraz. His parents don’t have the title to their land, and he’s working to obtain it. I’ve read about many Indigenous people in Peru who don’t have legal rights to the land they’ve lived and worked on for generations. There have been social movements to transfer property ownership from the wealthy to those who farm the land—but the process remains fraught. I don’t understand it. Leifer’s parents built a home here. They’ve worked this land for decades. Not having papers to prove ownership worries the family. Leifer spent the morning going through documents with his father. It looks like a long and difficult road ahead.

I can describe Peru, but it’s hard to name things. I question the quality of my observations—these new eyes trying to take in a culture that has existed for so long. I feel heartsick. I wonder how I’ll face the coming days and the return to a place that’s supposedly our home. But we were told we had to leave by June 5th, and I don’t want to have more headaches later.

The day of Leifer’s green card interview in February still feels like yesterday. I hadn’t heard from him in hours. He wasn’t answering his phone. When the call finally came, he asked, “Are you with your mom?” Time slowed. I was driving—arms and legs on autopilot. I was at the stoplight on the way to Half Moon Bay, to Enzo’s school, the library, Leif’s soccer practice. But suddenly, none of those things felt like they would be ours anymore.

My husband has so many strikes against him in the eyes of the U.S. immigration system—he is brown, he is poor, and he came to the U.S. with very little formal education. Now he’s a father to three incredible boys. He’s a successful small business owner. He pays his taxes. He follows the law. How can anyone look at our family and still choose to tear us apart? But this isn’t the first time our family has been torn apart. His sisters' visas to visit the U.S. have been denied too.

As our return to the U.S. approaches, I think about what I can do to bring Leifer home. I can write letters. I can protest outside USCIS. I can sue the U.S. government. My mind spins with possibilities. Something went wrong in his case. His lawyer says it’s difficult—but there is still a path forward. Still, what assurance do I have that this won’t happen again? I don’t understand how Leifer’s waivers were approved, yet at the end of the process, the “wrong” waivers were submitted. Something doesn’t add up. Someone needed to meet a quota. Someone had to deport more immigrants to keep their job. There are countless stories like Leifer’s—fathers, business owners, taxpayers with no criminal records—being forced out of the country. And there are children like ours, wondering what happened to their dad. Do people even know what’s happening? There’s already too little support for mothers in America.

Thank you all for your support. Your words and emails have meant the world to me and my family.

Cue my 8 a.m. rush of tears. Leifer asking you if you're with your mom. Breaks my heart.

Hi Abby, Wow. It is beyond bewildering what has happened to Liefer and your family over this. I can't help but place the blame with Trump and his immoral and sadistic "policies". Inflicting suffering seems the point. No one is safer or better off. If you need anything that we have or can do just say so. We could pick you up at the airport if that is helpful. We care about you and your family. Love to you and yours.